[Intro Plays]

[The sound of a campfire is accompanied by bass heavy droning in the background, and the sound of a beating heart. Echoing whispers and screams punctuate the notes. A metal door slams in the distance and sinister laughter fades in from the background]

[Story]

Tales Under A Broken Sky – Episode 09 – Christabel – By Samuel Taylor Coleridge

PART II

Each matin bell, the Baron saith,

[Sounds of bells]

Knells us back to a world of death.

These words Sir Leoline first said,

When he rose and found his lady dead:

These words Sir Leoline will say

Many a morn to his dying day!

And hence the custom and law began

That still at dawn the sacristan,

Who duly pulls the heavy bell,

Five and forty beads must tell

Between each stroke—a warning knell,

Which not a soul can choose but hear

From Bratha Head to Wyndermere.

Saith Bracy the bard, So let it knell!

And let the drowsy sacristan

Still count as slowly as he can!

There is no lack of such, I ween,

As well fill up the space between.

In Langdale Pike and Witch’s Lair,

And Dungeon-ghyll so foully rent,

With ropes of rock and bells of air

Three sinful sextons’ ghosts are pent,

Who all give back, one after t’other,

The death-note to their living brother;

And oft too, by the knell offended,

Just as their one! two! three! is ended,

The devil mocks the doleful tale

With a merry peal from Borodale.

[Lighter Bells ringing]

[Background music. Rumbling, airy bass with bright chimes ringing intermittently]

The air is still! through mist and cloud

That merry peal comes ringing loud;

And Geraldine shakes off her dread,

And rises lightly from the bed;

[Sounds of sheets and dressing]

Puts on her silken vestments white,

And tricks her hair in lovely plight,

And nothing doubting of her spell

Awakens the lady Christabel.

[Soft yawn on waking]

‘Sleep you, sweet lady Christabel?

I trust that you have rested well.’

And Christabel awoke and spied

The same who lay down by her side—

O rather say, the same whom she

Raised up beneath the old oak tree!

Nay, fairer yet! and yet more fair!

For she belike hath drunken deep

Of all the blessedness of sleep!

And while she spake, her looks, her air

Such gentle thankfulness declare,

That (so it seemed) her girded vests

Grew tight beneath her heaving breasts.

‘Sure I have sinn’d!’ said Christabel,

‘Now heaven be praised if all be well!’

And in low faltering tones, yet sweet,

Did she the lofty lady greet

With such perplexity of mind

As dreams too lively leave behind.

So quickly she rose, and quickly arrayed

[Sounds of sheets and dressing]

Her maiden limbs, and having prayed

That He, who on the cross did groan,

Might wash away her sins unknown,

She forthwith led fair Geraldine

To meet her sire, Sir Leoline.

[Sound of door opening and closing]

[Music fades in, soft, ethereal synth keys and low bass]

The lovely maid and the lady tall

Are pacing both into the hall,

[Sounds of steps on stone]

And pacing on through page and groom,

Enter the Baron’s presence-room.

[Sounds of Door opening and closing]

The Baron rose, and while he prest

His gentle daughter to his breast,

With cheerful wonder in his eyes

The lady Geraldine espies,

And gave such welcome to the same,

As might beseem so bright a dame!

[Background music. Airy, droning woodwind instruments]

But when he heard the lady’s tale,

And when she told her father’s name,

Why waxed Sir Leoline so pale,

Murmuring o’er the name again,

Lord Roland de Vaux of Tryermaine?

Alas! they had been friends in youth;

But whispering tongues can poison truth;

And constancy lives in realms above;

And life is thorny; and youth is vain;

And to be wroth with one we love

Doth work like madness in the brain.

And thus it chanced, as I divine,

With Roland and Sir Leoline.

Each spake words of high disdain

And insult to his heart’s best brother:

They parted—ne’er to meet again!

But never either found another

To free the hollow heart from paining—

They stood aloof, the scars remaining,

Like cliffs which had been rent asunder;

A dreary sea now flows between;—

But neither heat, nor frost, nor thunder,

Shall wholly do away, I ween,

The marks of that which once hath been.

Sir Leoline, a moment’s space,

Stood gazing on the damsel’s face:

And the youthful Lord of Tryermaine

Came back upon his heart again.

[Background music. Uplifting, rising strings]

O then the Baron forgot his age,

His noble heart swelled high with rage;

He swore by the wounds in Jesu’s side

He would proclaim it far and wide,

With trump and solemn heraldry,

That they, who thus had wronged the dame,

Were base as spotted infamy!

‘And if they dare deny the same,

My herald shall appoint a week,

And let the recreant traitors seek

My tourney court—that there and then

I may dislodge their reptile souls

From the bodies and forms of men!’

He spake: his eye in lightning rolls!

For the lady was ruthlessly seized; and he kenned

In the beautiful lady the child of his friend!

[Background music. Airy woodwind instruments return]

And now the tears were on his face,

And fondly in his arms he took

Fair Geraldine, who met the embrace,

Prolonging it with joyous look.

Which when she viewed, a vision fell

Upon the soul of Christabel,

The vision of fear, the touch and pain!

She shrunk and shuddered, and saw again—

(Ah, woe is me! Was it for thee,

Thou gentle maid! such sights to see?)

Again she saw that bosom old,

Again she felt that bosom cold,

And drew in her breath with a hissing sound:

Whereat the Knight turned wildly round,

And nothing saw, but his own sweet maid

With eyes upraised, as one that prayed.

The touch, the sight, had passed away,

And in its stead that vision blest,

Which comforted her after-rest

While in the lady’s arms she lay,

Had put a rapture in her breast,

And on her lips and o’er her eyes

Spread smiles like light!

With new surprise,

‘What ails then my belovèd child?

The Baron said—His daughter mild

Made answer, ‘All will yet be well!’

I ween, she had no power to tell

Aught else: so mighty was the spell.

Yet he, who saw this Geraldine,

Had deemed her sure a thing divine:

Such sorrow with such grace she blended,

As if she feared she had offended

Sweet Christabel, that gentle maid!

And with such lowly tones she prayed

She might be sent without delay

Home to her father’s mansion.

‘Nay!

Nay, by my soul!’ said Leoline.

[Background Music. Rising strings return]

[Sound of horses. Echoy and distant]

‘Ho! Bracy the bard, the charge be thine!

Go thou, with sweet music and loud,

And take two steeds with trappings proud,

And take the youth whom thou lov’st best

To bear thy harp, and learn thy song,

And clothe you both in solemn vest,

And over the mountains haste along,

Lest wandering folk, that are abroad,

Detain you on the valley road.

‘And when he has crossed the Irthing flood,

My merry bard! he hastes, he hastes

Up Knorren Moor, through Halegarth Wood,

And reaches soon that castle good

Which stands and threatens Scotland’s wastes.

[Sound of horses, echoey and distant]

‘Bard Bracy! bard Bracy! your horses are fleet,

Ye must ride up the hall, your music so sweet,

More loud than your horses’ echoing feet!

And loud and loud to Lord Roland call,

Thy daughter is safe in Langdale hall!

Thy beautiful daughter is safe and free—

Sir Leoline greets thee thus through me!

He bids thee come without delay

With all thy numerous array

And take thy lovely daughter home:

And he will meet thee on the way

[Sound of marching and horses galloping, distant and echoing]

With all his numerous array

White with their panting palfreys’ foam:

And, by mine honour! I will say,

That I repent me of the day

When I spake words of fierce disdain

To Roland de Vaux of Tryermaine!—

—For since that evil hour hath flown,

Many a summer’s sun hath shone;

Yet ne’er found I a friend again

Like Roland de Vaux of Tryermaine.

The lady fell, and clasped his knees,

Her face upraised, her eyes o’erflowing;

[Background music. Airy woodwind instruments return]

And Bracy replied, with faltering voice,

His gracious Hail on all bestowing!—

‘Thy words, thou sire of Christabel,

Are sweeter than my harp can tell;

Yet might I gain a boon of thee,

[Background music. Ethereal strings droning]

This day my journey should not be,

So strange a dream hath come to me,

That I had vowed with music loud

To clear yon wood from thing unblest.

Warned by a vision in my rest!

For in my sleep I saw that dove,

[Dove Call, flapping wings]

That gentle bird, whom thou dost love,

And call’st by thy own daughter’s name—

Sir Leoline! I saw the same

Fluttering, and uttering fearful moan,

Among the green herbs in the forest alone.

Which when I saw and when I heard,

I wonder’d what might ail the bird;

For nothing near it could I see

Save the grass and green herbs underneath the old tree.

‘And in my dream methought I went

To search out what might there be found;

And what the sweet bird’s trouble meant,

That thus lay fluttering on the ground.

I went and peered, and could descry

No cause for her distressful cry;

But yet for her dear lady’s sake

[Hissing and rustling of snake]

I stooped, methought, the dove to take,

When lo! I saw a bright green snake

Coiled around its wings and neck.

Green as the herbs on which it couched,

Close by the dove’s its head it crouched;

And with the dove it heaves and stirs,

Swelling its neck as she swelled hers!

I woke; it was the midnight hour,

The clock was echoing in the tower;

[Background music. Fades to airy woodwind instruments again]

But though my slumber was gone by,

This dream it would not pass away—

It seems to live upon my eye!

And thence I vowed this self-same day

With music strong and saintly song

To wander through the forest bare,

Lest aught unholy loiter there.’

Thus Bracy said: the Baron, the while,

Half-listening heard him with a smile;

Then turned to Lady Geraldine,

His eyes made up of wonder and love;

And said in courtly accents fine,

‘Sweet maid, Lord Roland’s beauteous dove,

With arms more strong than harp or song,

Thy sire and I will crush the snake!’

He kissed her forehead as he spake,

And Geraldine in maiden wise

Casting down her large bright eyes,

With blushing cheek and courtesy fine

She turned her from Sir Leoline;

Softly gathering up her train,

That o’er her right arm fell again;

And folded her arms across her chest,

And couched her head upon her breast,

And looked askance at Christabel

Jesu, Maria, shield her well!

[Background music. Deep booming in the background, vibrato heavy bass, distant ghostly screams]

A snake’s small eye blinks dull and shy;

And the lady’s eyes they shrunk in her head,

Each shrunk up to a serpent’s eye

And with somewhat of malice, and more of dread,

At Christabel she looked askance!—

One moment—and the sight was fled!

But Christabel in dizzy trance

Stumbling on the unsteady ground

Shuddered aloud, with a hissing sound;

[Surprised female gasp]

And Geraldine again turned round,

And like a thing, that sought relief,

Full of wonder and full of grief,

She rolled her large bright eyes divine

Wildly on Sir Leoline.

The maid, alas! her thoughts are gone,

She nothing sees—no sight but one!

The maid, devoid of guile and sin,

I know not how, in fearful wise,

So deeply she had drunken in

That look, those shrunken serpent eyes,

That all her features were resigned

To this sole image in her mind:

And passively did imitate

That look of dull and treacherous hate!

And thus she stood, in dizzy trance;

Still picturing that look askance

With forced unconscious sympathy

Full before her father’s view—

As far as such a look could be

In eyes so innocent and blue!

And when the trance was o’er, the maid

Paused awhile, and inly prayed:

Then falling at the Baron’s feet,

‘By my mother’s soul do I entreat

That thou this woman send away!’

She said: and more she could not say:

For what she knew she could not tell,

O’er-mastered by the mighty spell.

Why is thy cheek so wan and wild,

Sir Leoline? Thy only child

Lies at thy feet, thy joy, thy pride,

So fair, so innocent, so mild;

The same, for whom thy lady died!

O by the pangs of her dead mother

Think thou no evil of thy child!

For her, and thee, and for no other,

She prayed the moment ere she died:

Prayed that the babe for whom she died,

Might prove her dear lord’s joy and pride!

That prayer her deadly pangs beguiled,

Sir Leoline!

And wouldst thou wrong thy only child,

Her child and thine?

Within the Baron’s heart and brain

If thoughts, like these, had any share,

They only swelled his rage and pain,

And did but work confusion there.

His heart was cleft with pain and rage,

His cheeks they quivered, his eyes were wild,

Dishonoured thus in his old age;

Dishonoured by his only child,

And all his hospitality

To the wronged daughter of his friend

By more than woman’s jealousy

Brought thus to a disgraceful end—

He rolled his eye with stern regard

Upon the gentle minstrel bard,

And said in tones abrupt, austere—

‘Why, Bracy! dost thou loiter here?

I bade thee hence!’ The bard obeyed;

And turning from his own sweet maid,

The agèd knight, Sir Leoline,

Led forth the lady Geraldine!

[Music Fades]

[Footsteps on Stone. Door opens and closes]

THE CONCLUSION TO PART II

[Background music fades in, soft, ethereal synth keys and low bass]

A little child, a limber elf,

Singing, dancing to itself,

A fairy thing with red round cheeks,

That always finds, and never seeks,

Makes such a vision to the sight

As fills a father’s eyes with light;

And pleasures flow in so thick and fast

Upon his heart, that he at last

Must needs express his love’s excess

With words of unmeant bitterness.

Perhaps ’tis pretty to force together

Thoughts so all unlike each other;

To mutter and mock a broken charm,

To dally with wrong that does no harm.

Perhaps ’tis tender too and pretty

At each wild word to feel within

A sweet recoil of love and pity.

And what, if in a world of sin

(O sorrow and shame should this be true!)

Such giddiness of heart and brain

Comes seldom save from rage and pain,

So talks as it ‘s most used to do.

[Background]

Good evening, and welcome to Episode 09 of Tales Under A Broken Sky. I am your host Keith, and I hope you enjoyed this week’s episode.

So, here’s me trying to get back on track with my release schedule. I will probably try to get the next episode out in under the usual fortnightly timeline, but I don’t want to make any promises in that regard as the production process on it is going to be quite involved and a bit more complex than anything else I have attempted so far. There are multiple different viewpoints and I will be doing some funky work on some of the vocals as well. I’m looking at probably having maybe four distinct backing tracks for different parts on top of all of that as well. It’s a lot of work, but this will be the first release that I have purely written with the podcast in mind rather than something that has been sitting in a notebook for a few years. I’m really looking forward to this one, I feel like I’m starting to find a groove with writing new material, and I am excited with the way it is turning out so far. More on that in the next episode!

So! This was the second half of the narrative poem “Christabel” and this section is much more dialogue heavy than the previous, which is one of the reasons I decided to split this reading in half. I found it very long, especially when I was recording, and I know that when I was listening back over it and editing, my own attention started to waver when listening to the rhyme and meter for over forty minutes. Not that the dialogue sections are boring, they are wonderfully dramatic, as befits such a piece in my opinion, especially the character of Sir Leoline. It is not hard to visualise the grandiose gestures and atmosphere of the room during this piece.

Christabel’s role in this scene is tantalisingly foreboding, especially as she spends most of the scene effectively gagged by Geraldine’s magic. And when she is finally able to speak, her concerns fall on deaf ears. Bracy’s dialogue in this section underpins this feeling, his prophetic dream, clearly references Christabel’s dilemma, in the biblical analogy of the serpent in the woods.

And this brings us to a major crux with regards this piece. If it feels unfinished, that is because, well, it is. As much as I enjoyed the content of the piece, the foreboding atmosphere, the creeping feeling of danger and unease, the feeling that I felt the most at the end of this project was regret, or maybe pending regret might be more accurate. As someone who spends a large, if not majority of their time writing, thinking about writing, working through ideas and plots, not finishing something seems like a nightmare.

I know I for one, am terrible for starting new projects, although (and this is a mostly truthful admission) these are usually started just to get some part of the idea down on paper before I forget something I would rather not. Currently I actually have two complete manuscripts, one of which is getting really close to the level of polish and completeness that I want before I go looking for the “Holy Grail” of publication, the other is a mess of scribbles and red notes about rewrites, added/removed scenes and fairly large sections of reworking.

Outside of those I have various pieces of writing, of various lengths, and various states of planning. In my own mind, these matter less to me than finishing the two “complete” manuscripts. These have complete stories and the thought of them never seeing the light of day has become horrifying. I am sure I will feel the same way about some of the other manuscripts as they progress further, but for now, I am quite relaxed in my approach to them, in opposition to the sense of urgency I feel with regards, one manuscript in particular, that I am really close to final editing on.

As unsatisfying as an unfinished story might be for the reader, a feeling made blatantly obvious when one looks at the rather testy and vocal concerns of George R.R. Martin fans, I don’t have to imagine the existential terror that follows the prospect of a writer leaving a story they are invested in unfinished. To think that Robert Jordan spent his last months preparing notes and manuscripts so someone could finish The Wheel of Time in the face of his own looming death, shows the emotional labour we invest in our characters and stories.

I think as readers we have to understand something important; the writer, is very often not writing for the reader, often they are writing for themselves. Or at the very least, as much for themselves as for the reader.

Storytelling is an art, and has its own kind of magic. We can spend years with characters in the books we read. Oftentimes, growing up alongside them. I came to the Wheel of Time late, book nine was already published when I came to the series, but I was in my teens and the books were a constant companion to me for over a decade before the last book was released. We come to know the characters, often in ways that we don’t even know the people in our own lives. So it’s no wonder the strong feelings felt about stories that drag out across decades. For the writer, their connection to their own characters is even stronger. Consider all the unspoken character development, the little things that are unsaid and unwritten that inform their personalities and actions.

Writing is an act of creation, of creating worlds and the people that populate them. It might actually be as close to the proverbial “divine” that any of us can achieve. It might be fiction, but does it make it any less real.

Until next time.

[CTA]

Thank you for listening to Episode 09 of Tales Under a Broken Sky, I hoped you enjoyed this weeks production as much as I enjoyed reading and recording it.

If you did enjoy it, please consider subscribing to the podcast on your platform of choice, and leaving a rating and/or review.

Thank you again for your time. Stay tuned to hear a brief trailer for the next episode

[Episode 02 Trailer Plays]

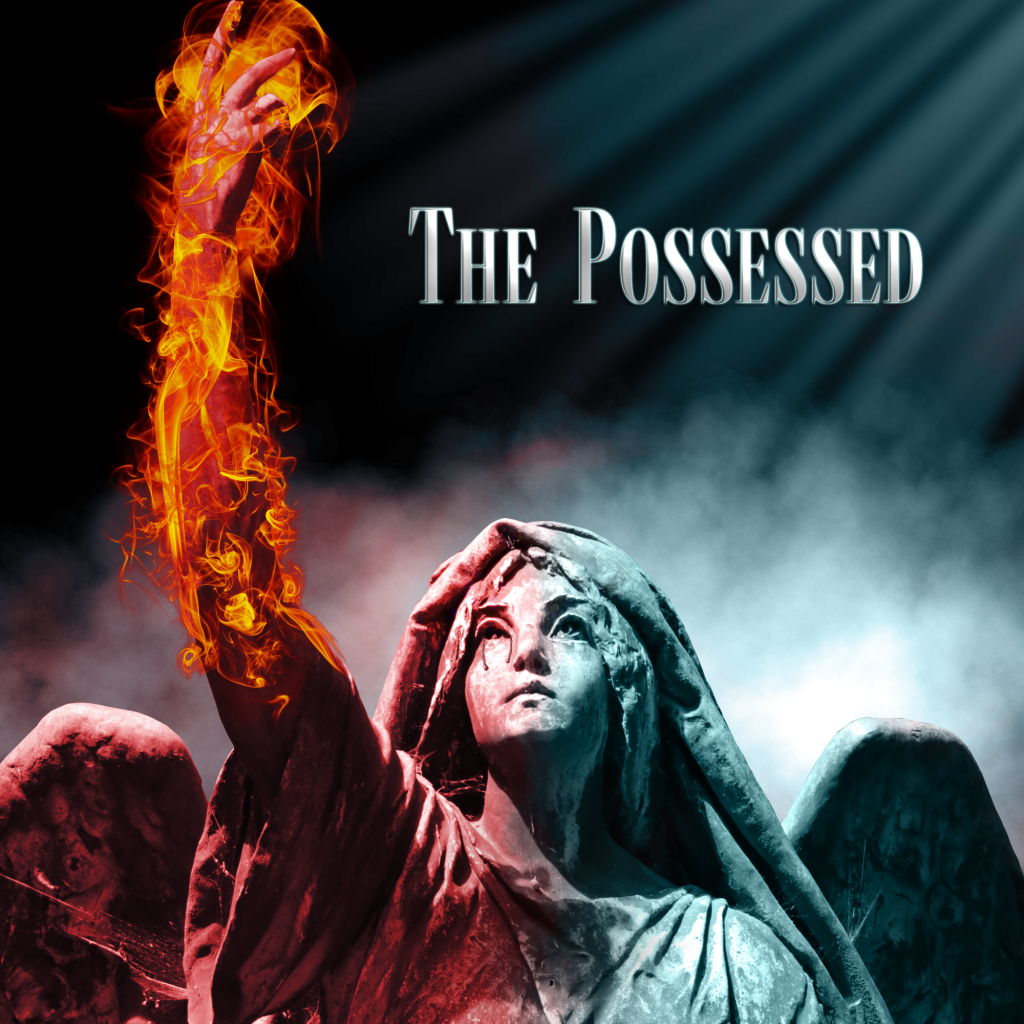

Tales Under A Broken Sky – Episode 10 – The Possessed (Part 01)

[Sound of soldiers marching in the background]

[Background music, droning synth bass with echoing banging in the background]

Anger.

Hatred.

Fear.

Supplication.

Power.

[Sound of political rally in the background. A speaker and a crowd cheering]

A thrill of pleasure ran through the man standing in the shadow of the blood red banner.

Oh! the sacred profanity of it all. Such a wondrous, savage lust.

The crowd spread out across the square stood silent, locked in rapt attention, as their “Great Leader” spewed violence and vitriol from his imagined pulpit. Thousands upon thousands of people, who on another day would have denied such thoughts, cheered and celebrated his words as if he spoke some essential truth. Timeless knowledge and wisdom that only they were privy to. The Chosen.

The man in the shadows smiled.

How easy it had been. A whispered word in the right ear, a little favour here, a minor promise there. The odd string, plucked with the precision of a master musician. The man was a fool, of course. But who better to manipulate. Who better to mould and shape into the tool he had needed.

Another tingle of pleasure rushed from his crotch to his throat, and he allowed himself a soft moan.

All of those people, ready to kill, murder, torture and maim. Prepared to betray their friends, colleagues, neighbours and families. Oh, what a beauteous, bountiful harvest. A nation prepared to sell their souls, and they didn’t even realise!

“Hah! Forgive them, Father, for they know not what they do.”

Ha! There would be no forgiveness here. No salvation. No eternal peace. Just war, and pain and suffering.

He purred in pleasure as a salute rippled through the crowd.

That was all it took, just a little nudge in the right direction, or the wrong one maybe. Sometimes it was almost too easy.

The man turned and slipped away quietly. His work here was done. It was time to turn his attention to some other, equally interesting, matters.

[Narration fades to Outro]

[Outro]

[The sound of a campfire is accompanied by bass heavy droning in the background, and the sound of a beating heart. Echoing whispers and screams punctuate the notes. A metal door slams in the distance and sinister laughter fades in from the background. All of the sounds are louder and closer, the atmosphere is more claustrophobic]

Leave a comment